Cyberspace . . . The realm of pure information, filling like a lake, siphoning the jangle of messages, transfiguring the physical landscapes . . . from all the inefficiencies, polutions (chemical and informational), and corruption attendant to the process of moving information attached to things -- from paper to brains -- across, over, and under the vast bumpy surface of the earth rather than letting it fly free in the soft hail of electrons that is cyberspace.

-Michael Benedikt, Cyberspace: First Steps

Cyberspace . . . organizations are seen as the organisms they are . . . money flowing in capillaries; obligations, contracts, accumulating (and the shadow of the IRS passes over). On the surface, small meetings are held in rooms, but they proceed in virtual rooms, larger, face to electronic face. On the surface, the building knows where you are and who.

-Michael Benedikt, Cyberspace: First Steps

Cyberspace . . . a graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding....

-William Gibson, Neuromancer

“Cyberspace” is a word from the pen of science fiction writer William Gibson (circa 1984) in his novels and short stories such as Neuromancer and Burning Chrome. 1 It is a word that beckons architects and planners from the furthest corners of the globe to the threshold of a new frontier in design and planning -- dangling at the cutting edge of traditional notions in space and time in a place that is nowhere and everywhere. It is a word that brings with it tremendous new considerations for a world centered around information technology and the possible social impacts it will have. Most importantly, it is a word calling for the rethinking of architecture’s role in a global information age.

t a b l e o f c o n t e n t s:

I. introduction to cyberspace

1. history of cyberspace

2. implications for a post-organic anthropology: the Gibsonian cultural model of

cyberspace

II. cyberspace and architecture in a global information age

III. cyberspace vs. real space: theories for design

1. design in real space: spatial mutants

2. new arenas for design: architects in cyberspace

IV. project description

1. design objectives

2. site description

Appendix A: site maps and photos

Appendix B: user hierarchical diagrams

Appendix C: spatial and functional requirements

Appendix D: notes and bibliography

I. Introduction

Try it,” Case said [holding out the electrodes of the cyberdeck]. The Zionite Aerol took the bank, put it on, and Case adjusted the trodes. He closed his eyes, Case hit the power stud. Aerol shuddered. Case jacked him back out. “What did you see, man?” “Babylon,” Aerol said, sadly, handing him the trodes and kicking off down the corridor. -William Gibson, Neuromancer

Gibson was the first to conceive of a place accessed through, sustained by, and generated from the collective data of “every computer in the human system.” Existing as a sort of “by-product” of the complexity of life on earth and the relentless interaction between its thinking beings, it emerges amid a new dimension. Unfolding in an endless digital landscape, it challenges traditional notions of space and time in a realm where data intrinsic to “invisible” social systems in this world are given visible, immersive representations. Through his various cyberpunk short stories and novels, he would eventually dub this place cyberspace.

the history of cyberspace

Initially, the word “cyberspace” may lead us to think only in terms of the present and future. However, cyberspace existed since the dawn of consciousness, albeit, not as we might have perceived in lieu of the modern technologies which brought it to our attention. Floating between the worlds of pure myth and pure fact, it began as the thinking mind’s ability to dream, wonder, imply, investigate, and conceive; an untimely “space” or realm of information created by the mental activity of conscious beings, but, at the same time, invisible and inaccessible to them.

Illustrating this concept, Sir Karl Popper, a renowned sociologist and theoretician, described three worlds which coexist parallel to one another, but not separately – connected by means of their own interaction:

World 1:

This is simply the physical world as we know it. It consists of everything around us which obey the physical laws of the universe and which operate under them; the world in which we, as individuals, interact with each other.

World 2:

The subjective world of consciousness in individual minds comprises the substance of world 2. It is the world in which thought and the imagination are fostered and dreams are wrought. As individuals, it is the only place we truly inhabit alone.

World 3:

This is the world of objective, public, and abstract social structures -- products of the minds of living creatures interacting with each other and with physical world 1.

Of particular interest is world three because, according to Popper, it has always existed as a sort of battery of collective conscience formed by the interaction of living, thinking beings in world 1. The by-products of these interactions manifest themselves in world three as “objective, public, and abstract social structures” such as social class, economics, law, etc... Due to their abstract quality, however, these structures could only be described using abstract symbols -- namely words -- in order to understand, or concretize, them. However, cyberspace presents us with the possibility of perceptually inhabiting this world, visualizing it for the first time, and implementing its final and ultimate manifestation.

Taking this idea further architect and theorist, Michael Benedikt, suggested four main threads which he believed intertwined throughout history to act as the vehicles through which man expressed, in world one, the workings of world three:

Thread One:

This evolved from the general consensus of early social groups about things which were merely accepted as “the case,” such as their early observations of the environment, and, of course, myths.

Thread Two:

Thread two spins from the history of media technology -- the means by which absent and/or abstract entities -- events, experiences, and ideas -- become symbolically represented, “fixed” into an accepting material (i.e texts, drawings, magnetic strips), and thus conserved through time and space.

Thread Three:

This thread is spun from the history of architecture. Some might argue here that architecture should belong to world one, perhaps due to its seemingly tangible physicality. Although it is true that architecture starts with man’s exile from nature, and with his need to meet certain immediate stresses such as climate, population, and defense, it is only with architecture that nature is co-opted, transformed, and made habitable. It is this separation from nature by means of architecture as a type of manifestation of humanity’s consciousness which sets it apart as an art, art as a product of abstract thought, and, thus, abstract thought as a structure of world three.

Benedikt explained architecture’s role in humanity’s undying struggle to break free of its earthly bonds. At first this was expressed through the countless projects begun and built in pursuit of the architectural pinnacle, the architecture of eternity, the architecture of the Kingdom of Heaven. Nonetheless, however vertical, colorful, or sculptural the architecture became, it still remained massive, solid and utterly bound to this world. But with the arrival of modernist theory, economic pressure to do more with less, and the availability of new materials, architecture began to take a different turn. It became lighter, wispier, whole walls reduced to reflective skins. This exploration in architecture, in regards to materiality, has continued in present day contemporary movements to the point of exhaustion. A question to ponder now is whether or not cyberspace is the next logical step for architecture.

Thread Four:

This thread is drawn from the larger history of mathematics. Benedikt explains that the “entities” of mathematics -- graphs, charts, computer representations of invisible physical processes -- are not entities at all. Rather, they are products of world three that have evolved as a result of our deductive intelligence. Here, mathematicians and architects are brought together under the common desire to conceive arithmetical information spatially.

As we see cyberspace has always existed, merely in different forms. World three (which, indeed, we name so for our own means of visualizing abstract concepts through abstract words) has been sought by humanity for millennia, whether it be through artistic expression, or objective social structures. Now, with present virtual technologies and a cyberspace that is under construction, we are faced with the end of this journey. The end, however, will be a time when world three is no longer merely sought after, but inhabited.

implications for a post- organic anthropology: the Gibsonian cultural model of cyberspace

In an essay on the technoculture depicted in Gibson’s vision for the near future, author and theorist David Thomas explores the notion of a post-organic anthropology for our society. He does this by comparing the post-industrial transubstantiation of the body in cyberspace to related social and symbolic transformations of the body in traditional rites of passage rituals characteristic of tribal societies, and, on a broader scale, pre-Industrial Revolution societies.3 The author explains how drawing direct parallels between the two may give foretelling insight of the culture transcending us in the future.

Demonstrating this concept, Thomas quotes sociologist Victor Turner (circa 1977): “For every major social formation, there is a dominant mode of public liminality, the subjunctive space/time that is the counterstroke to its pragmatic indicative texture.”4 Here the notion of “liminality” refers to the state or mode of transition/transposition experienced by an initiand (or group of initiands) between different stages of social existence or identity such as birth, puberty, marriage, and death. It is conceived as a “realm” in which the initiand is suspended and completely severed from any relations with the world of daily social structure. In this sense, s/he is in a sort of “exile” from identity. Before one may begin this liminal phase, however, one must first undergo the proper separation rites which are meant to prepare the individual for the transformation. Conversely, normalization rites come after the liminal phase to reinstate the individual to society. Some common examples of these rituals would be baby showers, weddings, birthdays, mourning periods for deceased loved ones, funerals, divorce, etc. . . The collective rites de passage rituals, then, act as mediators to ensure the initiand is properly removed, transposed between, and reinstated after the desired transformation has taken place without any residues of the previous existence or identity.

Though this theory does carry a slight “people as helpless pawns of circumstance” intonation, it draws interesting parallels between tribal/pre-Industrial Revolution social rituals and Gibsonian cyberspace. That is, the act of “jacking” in and out of cyberspace as Gibson depicted in his novels, though radically truncated versions, bare qualities similar to traditional rites de passage rituals. By jacking into cyberspace, the “initiand” performs an act similar to separation rites. Conversely, jacking out, is a version of normalization rites. The hardware (i.e. “cyberdeck” and “trodes” ) serves as access and egress. Cyberspace , then, would be similar to a state of liminality where the subject has no connection with his/her former self -- the biological body. Though this may seem to share some aspects with death and extra-bodily experiences, the important difference to remember is that, in cyberspace, return is possible. In this sense, it is not a parallel universe, but an alternate mode of being, a discontinuity of time and space in a pan human state.

This raises interesting issues of humanity’s religious tendencies with regards toGibsonian cyberspace. If, indeed, many acts performed in cyberspace reflect these ritualistic gestures and if cyberspace can be taken as a consensual hallucination which creates a discontinuity in space and time, then the argument could be made that cyberspace, as a sort of large caliber tribal ritual, will catalyze humanity’s religious tendencies, awaking them after years of desacralization from science. Already, virtual communities are forming on the internet under common creeds and beliefs, with deemed leaders and social structures. The talk of the ascension of humanity to a higher realm dominates topics of conversation on bulletin boards and newsgroups across the world. But, where will it really all lead? Will the individual finally be that of a free spirit? Or will we simply grow more isolated from one another in front of our computers as we become ultimately “in touch” with the world literally at our fingertips?

These questions are best considered by first understanding the behavior of those already living their lives as vicariously as possible online. Thomas offers a distinction between two types of behavior associated with, what he now refers to this rising technoculture as, a post-organic anthropology -- liminal and liminoid behavior. Liminal behavior is characteristic of tribal societies governed by the collective social. It is oriented by the central social group, everything done for the sake of that social group, and , thus, enhances the group as a whole. Liminoid behavior, on the other hand, forms independent of the social group. The individual is more non-contractual and modernistic -- modernistic behavior meaning the exaltation of the indicative mood. The liminoid sees the social as problem not datum. Though there is a mixture of both in today’s virtual communities, it can be said that the liminoid is rapidly encroaching upon the liminal.

We must realize that Gibson’s interpretation for the future, however exciting or opportunistically suggestive it may seem, possesses an intrinsically dystopic element as well.3 Though Gibson’s model has the potential of becoming a culturally creative arena in , what would seem, a given post industrial social context, it’s potential is thwarted by the liminoidal qualities of its nature. Both desperate and dismal, it is a future in which the celebration of individual spiritualism and the ascension of humanity is traded for a heritage of corporate hegemony and urban decay. In this post tribal, post liminal future, information is the key commodity and the individual an expendable component; cyberspace being nothing more than a locale for corporate contestatory economic activity. Desperate soles then attempt to flee the resulting intolerable reality, but instead fall into various states of spritual and moral degeneration. Here, there are only the technologically adept or the informationally inept . . . no exceptions . . .only expenditures.

If one considers today’s increasingly dominant and exclusive socioeconomic structures coupled with recent developments in information technology, such as virtual reality, digital communications, and the world wide web, Gibson’s vision may indeed be closer to actualization than we think. In fact, many aspects of Gibson’s stories are simply futuristic extensions of today’s truths. For instance, the “console cowboys” of Gibson’s novels are the counterparts of today’s hackers. Under the belief that all access to information should be free and with the technical knowledge to act, hackers today fight for a new social order all together. As their popular war cry goes, “Always yield to the hands-on imperative.”5 This operates under the pretense that information is not something which can be owned. A good example would be where a company is carrying information on you, such as your credit account, and wouldn’t allow you access. Since the credit is information on you, your own personal files, do you not have a right to access it? Can viewing information on yourself possibly infringe on other's rights? This demonstrates a type of system today that simply would not function in, or at least be counterproductive to, the future. How do we put a restriction on “intellectual property rights” when we’re not even sure what property is in this case or what those rights really are? In the same sense, those who do not have privileged access to information through filiation or who simply cannot afford the sophisticated equipment to access that knowledge today, will most likely not be able to tomorrow. Economics are a constant-- present or future. That is not likely to change.

With this in mind, cyberspace should be a realm accessible to all, not only the privileged. Virtual and real must complement each other rather than operate separately. In this way, we may avoid Gibson’s dystopic vision and , instead, realize cyberspace for its potential of benefitting humanity rather than engineering its demise. As stated by Thomas, “. . . we must seek alternative creative and spatial logics, social and cultural configurations.”6 Otherwise, cyberspace may only serve to elevate levels of corporate beuracracy rather than holding considerable promise for a new post-organic anthropology.

II. Cyberspace and architecture in a global information age

- The metropolis today is a classroom: the ads are its teachers. The traditional classroom is an obsolete detention home, a feudal dungeon. - Marshall McLuhan, Counterblast

When we ponder the question of architecture’s specific role in an information age, we should not only deal with buildings as singular entities, but rather we must consider the impact of a fully developed cyberspace on a broader scale, the scale of the urban fabric. In works such as Gibson’s novel, this manifested itself in the form of an urban dystopia. However, this vision was a direct result of corporate hegemony and an exclusive, inhumane cyberspace (see discussion in previous section). In consistency with this vision, therefore, architecture and urbanity are equally cold and brutal. However, there are interpretations of the future which do in fact observe architecture as a means of embracing technology through expression. In Lawrence G. Paul’s 1981 screenplay, Blade Runner (figures 1 and 2), we see an urban vision slightly different from that

figures 1 and 2: imagery from Blade Runner, 1981

of Gibson’s. Released before the idea of cyberspace, architecture here is centered around electronics technology as the key aesthetic motivation.

Though the urban context of Blade Runner does correspond with Gibson’s vision as a scene of overcrowding and decay , it also makes use of architecture as a form of iconography through electronics.10 In many respects, this makes sense for the architecture of the information age, and especially the architecture of cyberspace’s fruition even though this film was conceived without regard to such a concept. In his book, Iconography and Electronics Upon a Generic Architecture, Robert Venturi argues for an architecture which finally embraces “...electronic technology, scenographic imagery, and flexible iconography that itself celebrates [the] pluralities of cultures and contexts over time,” and whose content, “ accommodates our information age rather than our aged theorists.” 8 However, this sort of architectural treatment was a vision by architects for decades.

For instance, cities gradually came to be seen less as simple collections of streets, buildings, and parks, and more as “immense nodes of communication: messy nexuses of messages, storage and transportation facilities, massive education machines of their own complexity, involving equally all media, including buildings.”9 Archigram, a group of six architects operating between 1961 and 1974, was one such group. Their dream was of a city that built itself unpredictably, cybernetically, and of buildings that did not resist television, telephones, cars and advertising -- arguably some of the earliest forms of cyberspace -- but instead accommodated and played with them. “Label City” and “Instant City” (figures 4 and 5) are two visionary projects by Archigram which illustrate these ideals:

figures 3 and 4: Archigram’s “Label City”, 1972 and “Instant City”, 1973 respectively

Their work was on the cutting edge, and, at first, not greeted with open arms. They tended to upset people who still thought architecture was somehow a sacred discipline that should not be played with and certainly not placed at the some “level” as comics, television, rock and roll, and various other forms of popular cultural phenomena. Their beliefs that architecture could be more than just implied concepts -- that it could literally tell you something -- was too advanced for the times. However, as cyberspace transcends us, the need for new forms of communicatory logics and a new architectural language have made many of these principles valid and necessary.

III. cyberspace vs. real space: theories for design

A call to reconsider the role of architecture, even beyond Archigram’s dream, is more crucial than ever before. With the rapid onslaught of new developments in communications and informations technology, multi media, and virtual reality all pushing towards a unified cyberspace, the time for acceptance of architecture as mediator has come. Cyberspace and real space, their systems having reciprocal influence on each other, will and must reflect one another in their respective designs. Architects and designers must merge, disseminate, and proliferate the two realms into a mutual state of counter-influence. As we will see, this will require careful design considerations on both fronts.

Design in real space: spatial mutants

- Cyberspace will reconfigure the uses of physical spaces and real time slots. It will lead to the disintegration of many traditional building types and recombination of the remaining pieces with computational devices, telecommunications networks, and software to generate unprecedented mutants. -William J. Mitchell, “Virtual Architecture”

In real space, buildings must not stand idle -- ignorant of day-to-day information exchange by existing as none other than indifferent “people containers.” They must not simply house their programs behind inhibiting walls, in sterile offices and classrooms which provide no accommodation for innovative new technologies and new means of communication, thus hindering their evolution. Rather, buildings must funnel these currents of communication, intercept them at various levels and disseminate them among proper channels. They should act as “adaptive transmitters” to cyberspace by allowing for the uninterrupted exchange of information between both realms. The arrival of a new immersive, fully consensual cyberspace will see a culmination of this role.

Certain building types have already begun, in one way or another, to recombine their existing paradigms by accommodating technology in ways best suited to it. This trend is evident in building types centering around the exchange, distribution, consumption, and storage of information such as libraries, office buildings, post offices, and banks. In no place is this more apparent today, however, than in the changing workplace. Many enlightened corporations have begun reconfiguring their office environments in order to improve productivity and promote a sense of community among employees through special new technologically-oriented programs.

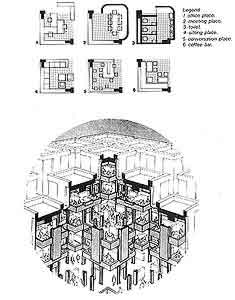

The idea of community in the workplace began as early as 1972 with the work of Dutch Architect Herman Hertzberger and his Centraal Beheer insurance company head quarters in Apeldorn, Holland (figures 5 - 7). While corporate America was busy marking the landscape with hermetically sealed office towers and rambling suburban complexes, Hertzberger set the precedent for a new type of office layout. Conceived as a “big house” for 1,000 people, the overall initiative was to create an environment that would foster creativity in a new office community.

figure 5: ground floor plan figure 6: cut-away axo figure7: view of atrium

Hertzberger’s design has had rippling effects in office planning. The need to accommodate technology while still promoting this sense of community has led the field back to the idea explored at Central Beheer. These changes are taking place mostly with companies who recognize the possible advantages of the information age, if prepared for correctly, as well as its possible ill effects if we use technology in a fashion which increases dispersion of skills and isolation of workers.

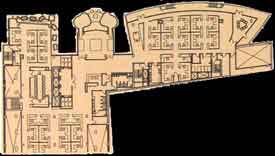

For instance, Chiat/Day, the ad agency that commissioned Frank Gehry to design its Santa Monica, California headquarters, recently brought in Lubowicki/Lanier to gut the regimented interiors and replace them with a, “. . .virtual agency, where creativity is best fostered by cross-fertilization. With no dedicated offices, the building, wired for all current and potential technologies, will house myriad team-orientedand common spaces . . .”11 (figures 8 and 9). This plan provides new types of work spaces such as “cockpit offices” and “work/eat areas” in a transformed office format resembling an “interior campus” of sorts. This new format, actually a result of the intensive research of BOSTI (the Buffalo Organization for Social

figure 8: Chiat/Day “before” plan figure 9: plan after renovations

and Technological Innovation), follows specific requisites of new construction. In the following excerpt from the March, 1994 issue of Progressive Architecture , Michael Brill discusses the BOSTI principles:

- New construction of offices . . . must accommodate the much wider variety of space types needed by vertically integrated and team-based organizations. They need offices, of course, but intermixed with spaces for training: laboratories; workshops; showrooms; media studios; research and development; production . . . and to accommodate both global business hours and extended “normal” hours. People must have access to late-night food and a range of off-hours amenity spaces and services . . . either in-building or nearby and safe where land is available. Both the spatial mix and need for amenities can be provided in a campus plan. . .

Some natural consequences of the changes we are experiencing are the loss of opportunities for informal learning (the way most things are learned in organizations), the loss of work-related social networks, [and] some psychic distancing from the organization. These happen because of shorter duration terms and decreased cycle times, more work in the field and home (and less in the office), folks electronically networked rather than spatially co-located. It is becoming very important to purposively design workplaces that maximize and support face-to-face contact of all kinds.

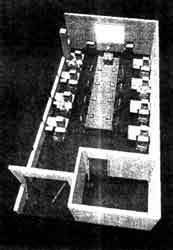

BOSTI principles are perhaps best exemplified by XEROX corporation’s AFI (Alternate Facilities Initiative) program.12 Instated under these same imperatives, XEROX has provided detailed plans for the design and renovation of all their corporate facilities. Figures 10 - 12 show the ideal floor plan layout for AFI as well as some 3D representations of these new unique work spaces.

figure 10: typical AFI floor plan

figures 11and 12: in-use demo, high performance learning center

The whole design is oriented under the idea of a campus plan. Open spaces act as commons areas which are the locales for creative group work. These are equipped with “tech tables” which provide digital outlets for laptops and other electronics. The layout of work spaces, such as cockpit offices and telebooths, are then strategically arranged around the open commons areas. Also, these work spaces are perfectly designed for given tasks. The employees simply choose which space is the most appropriate, and then use the space as long as necessary. This attention to detail is taken as far as placement of strategic niches in corridors (i.e. at corners of intersections, across from conference rooms) in hopes that even the productivity of chance meetings will be increased. In order to accomplish this goal, these niches are equipped with the necessary amenities such as writing surfaces, telephones, and digital outlets.

Another interesting idea of the AFI program is that of in-use demonstrations. By providing spaces such as the “in-use demo” room (refer to figure 11) XEROX brings the public directly into the heart of its operation. In programs such as AFI, this is a crucial complement. By allowing for public hands-on use and the communalization of people under the sign of technology, such programmatic configurations serve to bring the realms of technology and society (cyberspace and the real world) closer to a state of mutual coexistence.

New arenas for design: architects in cyberspace:

- In the same way that cities offer enough variety and detail for us to distinguish one space from another, and the formal structure of architecture makes space navigable, our disciplines can prevent the users of information from getting lost in cyberspace, which is a big place with few maps

-Peter Anders, “The Architecture of Cyberspace”

Like real space, cyberspace will require painstaking consideration in its design layout. Architects and planners, through their respective disciplines, will engage this task in an environment that is the embodiment of both function and form; a place the earliest modernists could only dream of. In cyberspace, however, we will not only realize the dream of modernism, but inhabit it in a world where data forms space rather than occupying it. Here, we will indulge and proliferate the imagination as we transcend the restraints of the ordinary world to bask in the non-space of the mind itself. Direction, in the physical sense, has no jurisdiction, action no reaction, if the desire so be. For this is a place where any traditional laws of the universe can be compromised; a place where a fifth dimension causes objects to fold and double over on themselves pulsating in rythmic sync with the fluctuating algorithms that give them life. Here, “. . . not only is real time an active concern of the architect, but the logistics of sustainable, transmissable illusion become as real as the most physical material constraints.”13 In cyberspace, data is the facility and imagination the vehicle by which we explore it.

The question may come to mind of what role architects will play in cyberspace. Why is there a need for this discipline at all? To answer this, one might consider a function buildings and cities serve in physical space. For instance, cities form distinct points on the surface of the earth. We use these distinct points to navigate between large distances via given transportation routes. As we move in toward a particular city , we are guided by the unique features of that city’s presence as a place (i.e. through streets, plazas, parks, etc.). If we continue further, the scale of spaces and points become smaller and more distinct until the whole system works its way down to the exact desired destination (i.e in a room in a building ). Here, architecture serves to convey complex information in a logical and organized manner so that we may navigate our way to a certain point. In this sense, buildings and cities provide the world’s most detailed navigation systems, and, as such, are widely perceived in terms of their navigational values. To put it simply, the job of architects in cyberspace will be to give complex data visual, readily knowable representations while still providing a pleasant and memorable experience.

In cyberspace, we will need similar mechanisms of orientation with which to navigate. Since there are no natural features, everything starting as a barren datascape awaiting form, we must rely on the disciplines of spatial organization in order to create a system of navigation similar to that which we experience through architecture in physical space, albeit under radically different paradigms. Researchers and developers who are already negotiating the parameters of cyberspace, have acknowledged the importance of architectural design in this realm. “We’ve looked at various classical information structures in information space,” says Per-Kristian Halvorsen, XEROX’s Palo Alto Research Center lab manager. “We’ve left the two-dimensional arena behind; we’re distinctly using three dimensions, but there we’ve looked at trees, various kinds of graphs, hierarchical information timeline presentations, and we have also experimentally merged it with images of buildings. It is a space organization problem. Whether it is an architectural problem, I don’t know, [but] that’s probably a useful paradigm to think of it in.”14

While conceding that cyberspace exists as yet only in a relatively crude form, Michael Benedikt believes that, with developments in VR and networking technology, “one might cogently argue that cyberspace is now under construction.”15 He says it is important at this early stage in cyberspace’s existence to agree on a set of principles that might be regarded as the “laws of “nature in this virtual world. Thus, he derives, what he calls, the Seven Principles of Cyberspace:

- Principle of exclusion - you cannot have two things in the same place at the same time.

- Principle of maximal exclusion - given any n-dimension state of a phenomenon to be represented, choose for space and time dimensions the set of dimensions that will minimize the number of violations of the principle of exclusion.

- Principle of indifference - the felt realness of the world depends on the degree of its indifference to the presence of a particular user and on its resistance to their desire.

- Principle of scale - the amount of (phenomenal) space in cyberspace is a function of the amount of information in cyberspace.

- Principle of transit - travel between two points in cyberspace should occur phenomenally through all intervening points and incur costs to the traveller proportional to some measure of the distance.

- Principle of personal visibility - individual users in/of cyberspace should be visible in some form and to all other users in the vicinity. Individual users may choose whether or not, and to what extent, to see/display any of the other users.

- Principle of commonality - virtual places should be “objective” for a defined community of users.

- List from “Cyberspace: First Steps”

Benedikt also goes on to explain the concept of giving three dimensional representations to complex data sets in cyberspace.

Although the design of cyberspace does conceivably allow for the complete departure from all laws of real space, certain fundamental rules must be honored: namely, those rules of real space that the body, through its various faculties, uses to navigate its environment. Once these criteria are established, we may then decide which rules to jettison for the sake of empowerment. Otherwise, an absolute departure from all laws of our world would lead to disorientation and, ultimately, vertigo.

In an article describing his program, Trans Terra Firma,16 Marcos Novak, another architect involved in this field, urges for a new architectural poetics which, not only rethink the role of architecture in cyberspace, but also transcend any preconceived notions of space and time in the Euclidean sense. He states that architecture since the end of classicism has been impotent in mending the rupture between its representations and how we actually know the world around us. This is because, as our modes of examining, experiencing, and understanding the physical world became more pluralistic (i.e. as we “extended” our senses with scientific oberservation -- electromagnetic field studies, relativity, quantum mechanics that led to today’s theories of hyperspace and stochastic universes), it created a condition that architecture, burdened by its materiality, could no longer follow. Here, Novak provides a few parameters for cyberspatial design:

The Dimension of Implicit Time:

Novak explains how the principles of “time-image” in cinematics relate to the architecture of cyberspace. Time-image is the technique of taking scenes out of place in a film and reconstituting them in manners which color the story with probable histories of possible futures. In cyberspace, architecture will need to take this concept into consideration, for there the concern of the architect will extend beyond just motion through space. It will include motion through time as well. This is because, in cyberspace, the environment itself may change or fluctuate its attributes relative to one’s time and position in space.

The Dimensions of Implicit Space:

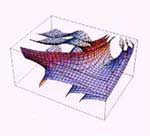

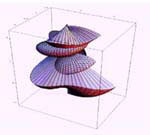

This has to do with the idea of, what Novak calls, “archimusic.” Since time and space can no longer be separated in cyberspace, he explains, then so too must we join the two arts which embody these two ideals -- architecture and music. Until now, we never had any way of inhabiting the imagination of this concept. While our sciences observed micro- and macroscopic regions of curved, higher dimensional space-time, we always built within the minimal capacity of our immediate senses. Now, however, we have a way of observing these realms through architecture which fluctuates rythmically with the systems it represents. Figures 26 - 28 are three images from Novak’s first Trans Terra Firma event at the Banf Centre for the Arts in Alberta, Canada which illustrate such concepts:

figures 25-27, left to right: isosurface, twist- shell spherical coordinate form, rippled isochamber

Here, we see various images from Novak’s “Dancing With The Virtual Dervish”, a program in which multiple users at the Trans Terra Firma event were able to interact with each other and with the architecture of virtual environments. These are designed through the analogy of sound as the result of different wave frequencies. Here, like sound, shapes can be controlled by adding or subtracting perturbations to the wave curves represented by the shapes (i.e. a sine wave). This principle illustrates what Novak means by “archimusic”. The creation of form in this manner will allow us to design an architecture appropriate to the complexities of cyberspace, relativity notwithstanding. In this way we might finally enhance our perception of spatial relations, “without always falling back on the sacred Euclidean geometry of the past.”

Though the area of design in cyberspace is still an open field, Novak and architects like him are leading the way in establishing new architectural expressions which are sure to have dramatic impacts on the profession. Only by pushing beyond traditional notions of time and space will we begin to understand our role as designers in a realm whose core logic is spatiotemporal representation. Thus necessitated by this are new concepts in space and form -- architecture now being much more than that of a utilitarian regime. We must reach beyond the static forms of Euclidean geometry and implied concepts, for the time has come at last to bridge the gap between the known systems of the universe and architectural poetics.

IV. Project discription

design objectives:

This thesis will implicitly study the ramifications of a fully immersive, transcontinental cyberspace on a post industrial, post liminal architecture and society. It will do this in an institute through whose very agency, and others like it, cyberspace exists; a research and production facility for cyberspace software systems. As a joint collaboration between Penn University students, professors, and XYZ Telecommunications Company personnel, this institute’s program will house functions existing in real time and real space, but with virtual extensions of themselves in cyberspace. This, in turn, will generate a civic/commercial portion which is meant to provide the public with hands-on access to the informations technology being produced at the institute. Though there will be a small retail portion, the institute’s main purpose will still be to allow free access to its facilities. In this way, it is hoped that, through education, the barriers between cyberspace and real space might be diminished by making the ladder less of an exclusive realm accessible only to the socially or technologically privileged.

As a result of it’s duality of functions, the program is actually separated into two parts (or two sides of one whole, if you will): a physical facility in real space, and a virtual one in cyberspace. It will therefore perform the key role of bringing the two worlds to a focal point where they might merge on a public scale. In this sense, it will serve as the “adaptive transmitter” through which activity and interactivity from real space will be transmuted into cyberspace (and vice versa). The institute’s two components and their respective design concepts are as follows:

The physical facility as:

* “adaptive transmitter” to cyberspace

* production cell generating cyberspace

* arrival and departure “terminal” for cyberspace

* marker in real space for this location

The virtual facility as:

* “adaptive transmitter” to real space

* storage and processing facility for data from real space

* data base and arrival facility for travellers in cyberspace

* destination in cyberspace for these coordinates

The physical facility retrieves data from its virtual facility in cyberspace. It then studies the data and produces operations which are fed back into cyberspace. At the same time, it acts as a “funnel” through which data and activity from real space can be transmitted/transmuted into cyberspace. Conversely, the institute’s virtual facility will receive data from its physical counterpart, storing and manifesting it in visible form as an accessible, inhabitable data base. This cyber facility will also serve as a social space containing public zones for general meeting and gathering (i.e. chat rooms, information center on the institute’s work, international library for the city of Philadelphia) as well as private zones for the institute’s use (i.e. teleconferencing chambers, private data or “cyber-study” zones, seminar rooms). All the while, this cyber-facility will constantly import data from cyberspace, combining it with data recieved from its real space counterpart, processing, and transmitting/transmuting it back to real space. Thus, it is a fully reciprocal relationship between the two components.

As we will see, the institute will enjoy an almost mirrored, if not completely merged, existence of functions in real space and cyberspace. Each side of this existence willl have direct influence on one another’s operations as they feed back and forth between the two realms. Each will exist simultaneously as entities of separate, yet parallel facets. Each will represent the ideals of the institute from which they were formed.

Between the two lies an infinitely small threshold -- visible, yet viable; real, yet minascule. It must be considered thoroughly. The design of an interface that allows people to “cross” its boundary as smoothly as possible is of vital importance. In order for the mergence of the two realms to be successful, users must not be bogged down by the technology which acts as their portal. This would create a feeling of uneasiness and discomfort, and thus the felt realness of the experience is drastically reduced in potency as well as effectiveness. It must not try to be overly pretentious.

site description:

The site is located near the campus of Penn University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (please refer to map and photos in Appendix A). The exact orientation lies within the athletic field area of Penn which is between the old Philadelphia Convention Center and the Schuykill river, separated from it by Interstate 95. The reason for the selection of this site is one of symbollic as well as functional significance:

- 1. Chronological Layering of Transport Systems:

In this area of the city, the primary land use has been for transport. Here bridges, tunnels, subways, railroads, expressways, and power lines interweave in a dense layering of steel, cable, and concrete. What is interesting, however, is the visible manner in which this layering has occurred over the years. First the railraod, then the subway, then electricity, vehicles, and interstates, all of them leaving their marks in a complex dialogue of movement (the abondoned subway station on the site reinforces these observations). This is testimony to humanity’s continuing transubstantiation through time and space: signal, image, letter, sound, moving image, live sound, live image, sense and action, intersense, interaction, presence, interpresence, and now telepresence. It is fitting, then, that this long history of our awareness of elsewhere should now have added to it our willingness to interact with everything in simultaneous existence.

2. Disparate Connection to the Urban Context

The question is not one of urban consideration: the city as place, negative spaces, relation to urban fabric, building as artifact, but rather it is one of intersection: the body transposed through telepresence, levels of transport, the collection and dissemination of information.. . . this site serves to enhance and elaborate these concepts. The straight line of infinity and the intersection for locale now displace space as merely a collection of solids and voids. For now space no longer exists in planar relativity between points, but as an incongruous permeation of visible (cars, trains, pedestrians, airplanes) and invisible movement (microwaves, fibre optics, cellular signals). Thus, though the physical building must certainly be designed for the body, considerations of traditional relationships to space will diminish with its new intermissiary state; caught between two worlds.

3. Zone of “Destination Points” in Real Space

With Amtrak’s 30th Street Station to the north, the direct connection to the Philadelphia International airport via Interstate 95 to the south, and two subway stations (one new, one abondoned) located directly on the site, the stories of arrival, departure, and motion-in-progress make this a proper location for the transport facility of the newest kind. Namely, the destination coordinate for cyberspace. Likewise, this building will be serving a similar function for users in real space such as the general public. For them, the civic/commercial portion of the institute will be analogous to a port terminal.

4. Proximity to Client

The site’s proximity to Penn University central campus is necessary for the students who will be using the facility. It also serves to solidify the operation of the institute by keeping it in close contact with cutting-edge intellectual development. In retrospect, the institute will help solidify the operations of the university by benefitting the educational realm as well.

Appendix D: bibliography

notes:

1. Cf. William Gibson’s Neuromancer, 1981, p. 125.

2. Cf. “Cyberspace: First Steps,” 1991, Michael Benedikt (ed.), p. 15.

3. Cf. David Thomas, “Old Rituals for New Space,” in “Cyberspace: First Steps.”

4. Turner speaks of these relationships in “Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology. Rice University Studies 60-4, 53-92.

5. In his essay “Property Rights, Privacy, etc.,” Mike Godwin discusses hacker raids on corporate systems in “High Noon on the Electronic Frontier: Conceptual Issues in Cyberspace,’ Peter Ludlow (ed.).

6. Cf. David Thomas, “Old Rituals for New Space.”

7. Robert Venturi calls for a new architectural expression in “Iconography and Electronics Upon A Generic Architecture,” 1996: pp. 6-10.

8. Cf. Robert Venturi, “Iconography and Electronics,” 1996.

9. Cf. Michael Benedikt, “Cyberspace: First Steps”, 1991.

11. Cf. Ziva Frieman, “The Changing Workplace” in Progressive Architecture, March, 1994:

pp.51-55

12. Cf. company manual for XEROX AFI guidelines, 1995

13. Cf. Peter Andrews in “The Architecture of Cyberspace,” in Progressive Architectue, October

1994, pp. 78-81, 106.

14. Cf. Per Kristian on Palo Alto in “Architecture in Cyberspace,” Progressive Architecture, 1994.

16. Cf. Marcos Novak. “Transmitting Architecture (Trans Terra firma). In Architectural Design,

1995, vol. 11-12.

references:

1. Benedikt, Michael (ed). “Cyberspace: First Steps.” The MIT Press. Cambridge, Mass.

1991: pp. 1- 210.

2. Gibson, William. Neuromancer. Berkely Publishing Group. Berkeley, Ca. 1984.

3. Slouka, Mark. “War of the Worlds: The High Tech Assault on Reality.” Harper Collins

Publishers. 1995.

4. Novak, Marcos. “Transmitting Architecture: Trans Terra Firma/Tidsvag Noll v2.0.”

Architectural Design. v. 11-12, 1994: pp 43- 7.

5. Ostler, Timothy. “Architecture in Cyberspace.” The Architects Journal . May, 1994: pp. 33-

5

6. XEROX Company Manual: “Alternative Facilities Iniciative: Field Office Facility Design

Concepts and Principles.” Feb. 3, 1995.

7. Ludlow, Peter (ed.). “High Noon on the Electronic Frontier.” MIT Press. Cambridge, Mass.

1996: pp. 1-6, 25-131.

8. Anders, Peter. “The Architecture of Cyberspace.” Progressive Architecture. Oct, 1994: pp

78-106.

9. Frieman, Ziva. “The Changing Workplace.” Progressive Architecture. March, 1994: pp

47-55.

10. Mitchell, William J. “ Virtual Architecture.” Architecture. Dec, 1993: pp.40-3.

11. Pastier, John. “Abstract Design for an Abstract Client.” Architecture.. May, 1987: 147- 49

12. Paul, Lawrence G.(prod.). Blade Runner. Universal Studios, 1981.

13. Venturi, Robert. “Iconography and Electronics Upon a Generic Architecture.” MIT Press,

Cambridge, Mass. 1996: pp. 1-15

Addendum (developments as of 12/5/96):

I have been formally asked by Dr. Norton of the Science, Technology, and Society department to add this addendum so the reader may be updated on the progress of this project. Please note, however, that these are the findings of my research by the end of Fall semester, 1996 and are by no means final. I will therefore add another addendum in April, 1997 at the thesis conclusion for further update on the project’s progress (in which case we may also argue the actual completedness of the project as I hope this will spark ongoing investigation in future generations of students). I will also add to this book volumes 2 and 3 which will comprise mostly visual documentation of the building. Volume 2 will document the stage the thesis was in at the end of Fall semester, 1996, and volume 3 will document the final stage of the thesis at the conclusion of Spring semester, 1997. Finally, when volume 2 is complete, I will add a commentary so to provide a complete depiction of the project. Until then, I will use this addendum to state only my ideas on the project by the end of Fall semester and will leave detailed descriptions of the building to the volume 2 commentary.

My investigations this past semester dealt mostly with the actual physical building. Though my original intentions had been to investigate both the physical and virtual sides of the institute simultaneously, this was not the case. However, this turned out to be a more appropriate means of investigation. Dealing with both sides of the program simultaneously was not only impractical from a time constraint standpoint, it also would’ve diverted my attention from the more important central theme of the project: developing a physical building for the institute in which people might congregate publically by facilitating the mergence of real space and cyberspace. I therefore concentrated most of my attention this semester on the development of the physical architecture of the institute. I intend to address the virtual side in more detail by the end of next semester.

Though I concentrated on developing the physical architecture first, this would not have been possible without the information I had collected from my cyberspace research. At first, I struggled with the form and exact function of the building. I was not sure exactly how to locate the building on the site and whether or not the building should contain certain functions as I had described in my program. Overall, I was lacking a system the building would follow in its design. After trying many tireless options, I finally settled on a certain metaphor drawn from cyberspace which seemed to yield a pertinent system for my building’ s design. The metaphor I am referring to is that of the cyberspace “matrix”.

In cyberspace, as described by Gibson as well as many scholars today who are debating the composition of cyberspace, we are faced with a barren datascape; a large, empty void which we must somehow give definition. To accomplish this, we begin by slicing it up the way we always have in history when attempting to define the undefined -- we impose a grid upon it. In cyberspace, then, we use this grid three-dimensionally (Cartesianally, of course) in order to plot points in space or, if you will, build within the grid. In other words, this grid forms the “bones” or “main structure” of cyberspace in which forms are made. This, of course, has implications and metaphors which touch down on many areas, but, for the purpose of the institute building, it possesses very relevant applications:

- 1. The institute building, as a place where cyberspace is made and its generating technology is housed, should somehow metaphorically relate tocyberspace since it does after all, as yet still in theory, have its virtualcounterpart there.

2. The technology of cyberspace will be the most self-inclusive, self-sustaining, and rapidly-evolving technology we have ever known.Therefore, the building type which will house its hardware, such as this institute, will have to be equally adaptable. This grid metaphor could then be carried over to the construction of the physical building by relating thecyberspace matrix grid to the steel-frame structural grid of the building.The grid module itself could be adjusted in dimensions to suit the purposes of the building. It could then be established as the permanent “bare bone” structure into which temporary structures and walls maybe inserted and removed according to the needs of the institute at anygiven time.

3. The grid of cyberspace represents a system bound to this world -- our world -- which we impose upon cyberspace for its familiarity as an ordering system (i.e. the grid of meridians and parallels we imposed upon the face of the globe, the grids of city streets we imposed when

plotting land, the Cartesian grid we imposed upon numeric functions, etc.). In other words, due to the infinite capabilities of cyberspace,we, as finite beings, use an aid which is familiar to us from this world; a“ladder” , if you will, which we climb to a higher level where we no longer need it. We then simply throw it away. This aid or “ladder”,then, would be the matrix grid for, one day, we will no longer need it to understand and create within cyberspace. Until that point, however, the grid represents a beginning which, if nothing else, is a means tofind an end. In the same sense, the structural grid of this new institutebuilding type is a means or frame work through which the institute will evolve to an end result or definition.

As we see, the matrix gid of cyberspace works well both symbolically and functionally as an ordering system for the macrostructure of the building. Another metaphor from cyberspace also allows for a pertinent ordering system in the building. If we recall section III of this book, I described Marcos Novak’s concept of “archimusic”. Here, Novak describes how the two arts embodying space and time, architecture and music, must be brought together to create a new art of space-time or archimusic in order to effectively communicate information in cyberspace which indeed entails consideration by the architect of movement through both space and time. But what if this concept could be used to provide the physical facilities of cyberspace institutes such as this with the flexibility they need? What if the physical architecture takes on a certain spatiality modeled after the temporal qualities of music to create a spatio-temporal architecture which is absolutely occasional or “of-the-moment”: capable of conforming to any needs at any given moment?

In order to better understand this, let us look at the nature of a musical score. The background rhythm in a score of music remains constant and could be taken as the “structure” of the score and thus we may apply this to the structure of the building. Next, the musical intonations and variations within the given score play around and against the rhythmic background fluctuating sometimes in sync, sometimes in opposition to, but always in and around the regular background rhythm. We may apply this to the temporal qualities of the free-formed structures built within and around the regular structural grid of the building. Lastly, much like the strategic syncopations which add dramatic and timely fluxuation to a musical score, these free-formed structures may themselves take on a dramatic quality of movement and pause by providing for surfaces that could be pushed, slided, hinged, attached, and detached at will in order to add the ultimate and final level of flexibility and spatio-temporality -- thus, archimusic applied to real space.

These concepts will, of course, receive further attention as the project continues to evolve. Due to this state of mid-development, then, it would be inappropriate here to go into further discussion of details within the building (which, not to mention, would be futile without proper visual reference). I will, therefore, reserve further discussion for volume 2.

The final evolution of the project can be found by clicking on the below image.

brand: University of Pennsylvania

work performed: concept, architectural design, drawing, paper modeling, 3d modeling, rendering

Design for an ubiquitous augmented environment for Penn University to host such events as global augmented reality tournaments, VR technology conventions in which guests can attend virtually as well as physically, and various other activities centered around the application and study of telepresence technologies.